Finding the grain of creative coding in 2002

Do you ever see a tweet that gets stuck in your brain for months? That happened to me two years ago with this one from Zach Lieberman:

Now, Zach is probably just talking about how much effort is spent trying to make fully-digital generative art look like physical media rather than trying to explore what makes the digital medium unique. I personally don't have a strong opinion on what aspect of the art one should focus on. But the question Zach poses—what is the "grain" of computational art?—is a brain worm for me.

What is grain?

For work on paper, you will see the texture of the paper in the negative space, and it will affect how the ink or graphite or whatever spreads on the page. You can work hard to avoid it, but by default, it's there. To me, that last part is what defines the metaphorical grain in Zach's tweet: it's the part of a medium that you get by default, unless you're specifically working to hide it.

I would say that the grain of painting as a medium is the brush stroke. At one point, painters painstakingly used sfumato to soften shading and chase realism, but after cameras were invented, works generally became more abstract. They embraced the fact that they are paint on a flat page and the texture that comes with that.

Each software framework is a medium

When translating this idea to the computer, it's hard to say what exactly everything has in common. I think that's because computational art is a bit too broad. On the computer, what software system you use will have a more profound effect on the output than the fact that it's on a computer because each one can give very different tools for you to work with.

A quick, obvious p5.js example: it's pretty easy to tell apart a 2D sketch from a WebGL sketch. One has primarily flat shapes; one has perspective or shading. This makes sense because in the latter, perspective happens automatically and you can add shading with a quick call to lights(), and in the former, doing that yourself would require hundreds of lines of manual code.

This framework-makes-the-grain idea is interesting and a little scary to me. I spend a lot of time building the WebGL mode of p5.js, so in a way, the decisions I make directly affect what art everyone makes with this tool. That's a lot of responsibility! I at least want to be thinking about the effects of my decisions, and to be informed about similar decisions made in the past. So I've gone down a rabbit hole learning about the history of internet art.

I bought an old computer to stay informed

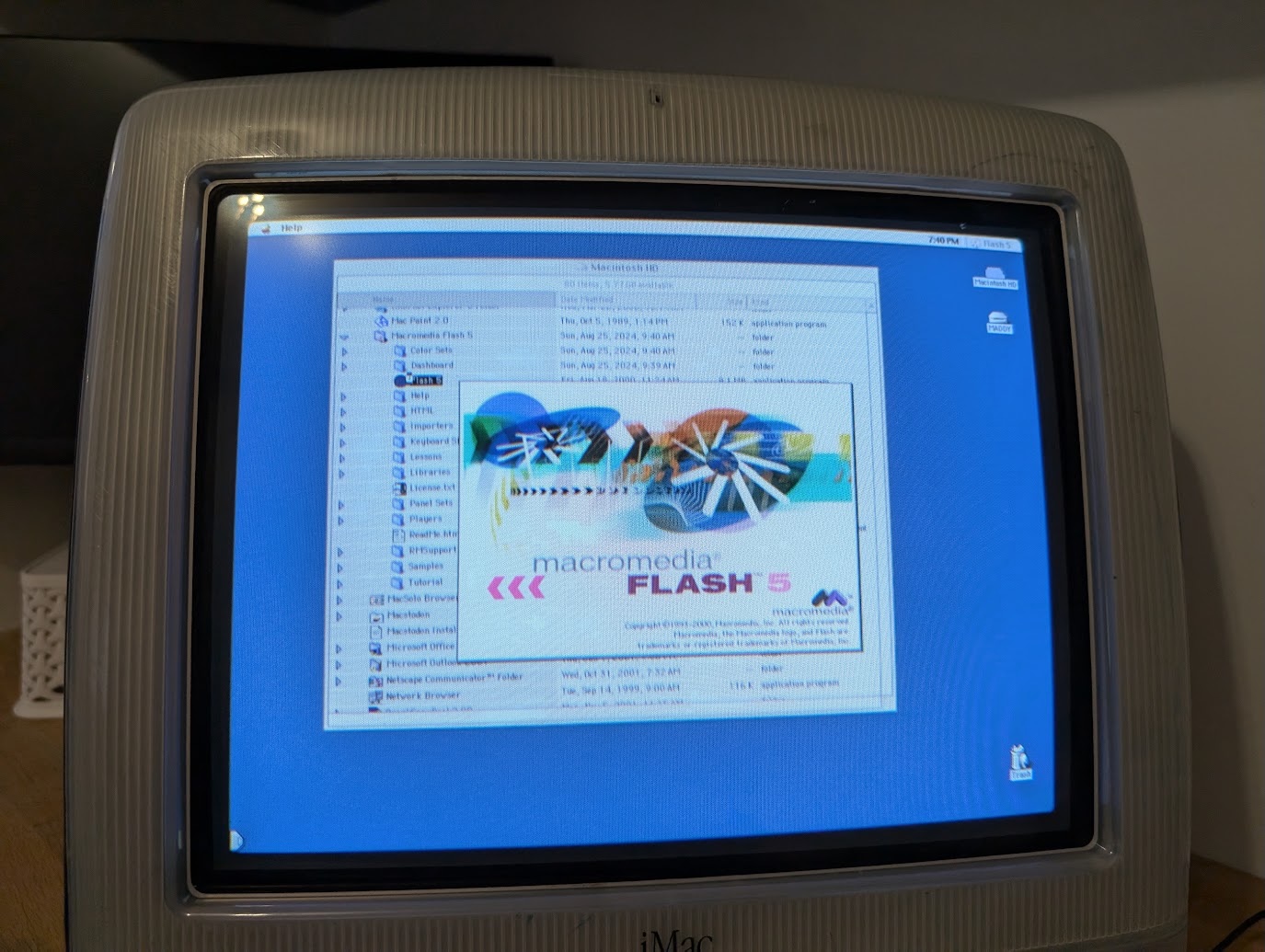

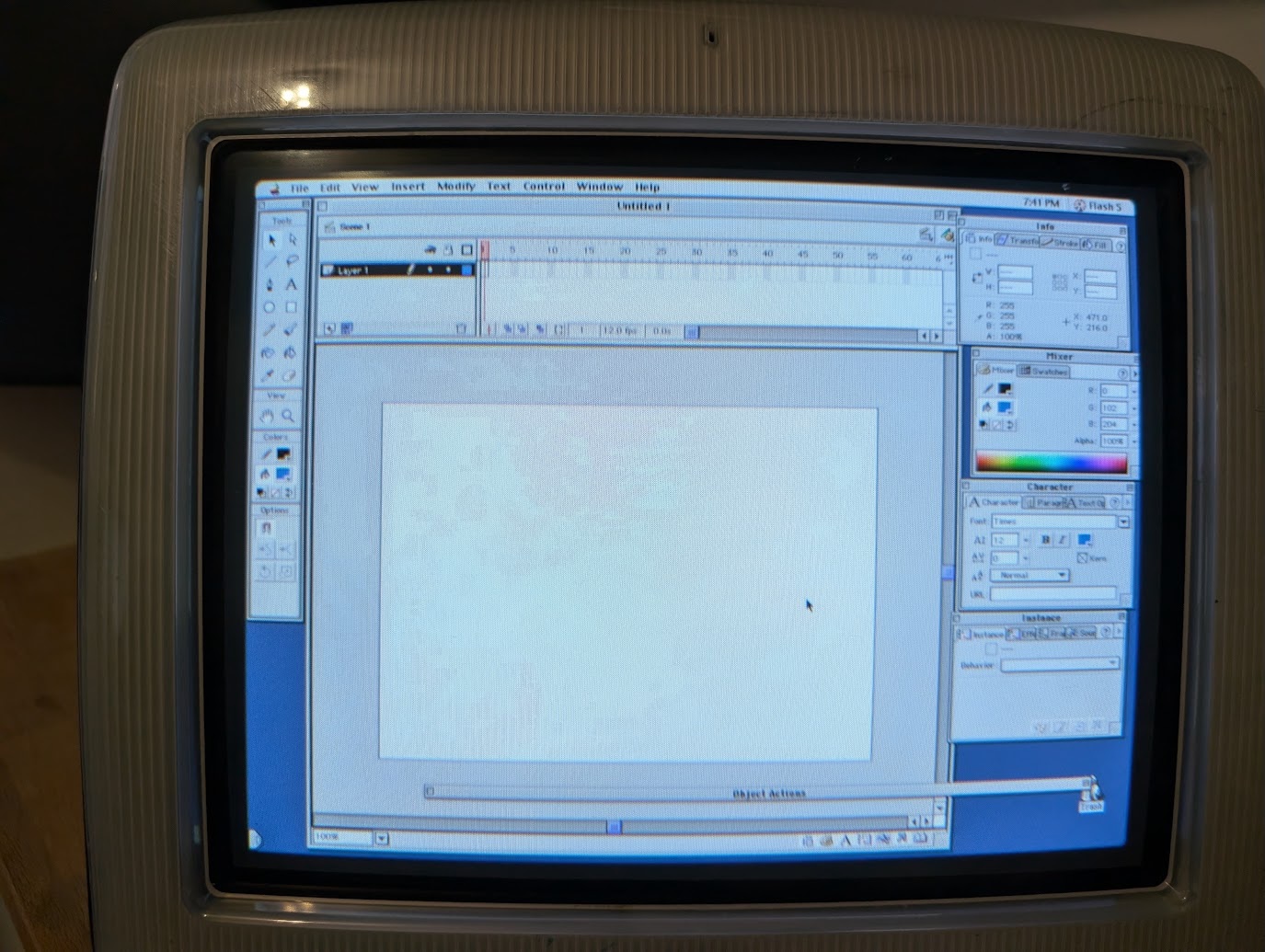

I picked this guy up from Facebook Marketplace.

The generative art scene I know now today is strongly tied to internet art. The works produced are not entirely meant to be consumed as pictures and video; they can be web pages you go to, where you can interact with them live. The first iMac came out in 1998 as an attempt to be an easy way to get onto the internet. Just plug in two cables, power and internet, and you're online! The "i" in "iMac" stands for internet! Using this machine gives me a crucial piece of context into the history of art native to the internet.

The claim about just plugging in a cable and being ready to go is, impressively, still basically true. The one major caveat is that it only knows HTTP. Most sites are served over HTTPS now, so if you're going to try this yourself, you'll need to run a proxy server on another computer to remove HTTPS, and then configure your Mac to go through that. But then after that, your more-than-two-decade-old machine is connected to the modern web!

Java and the web at the turn of the millennium

What would you do if it's around the year 2000 and you want to make interactive web art?

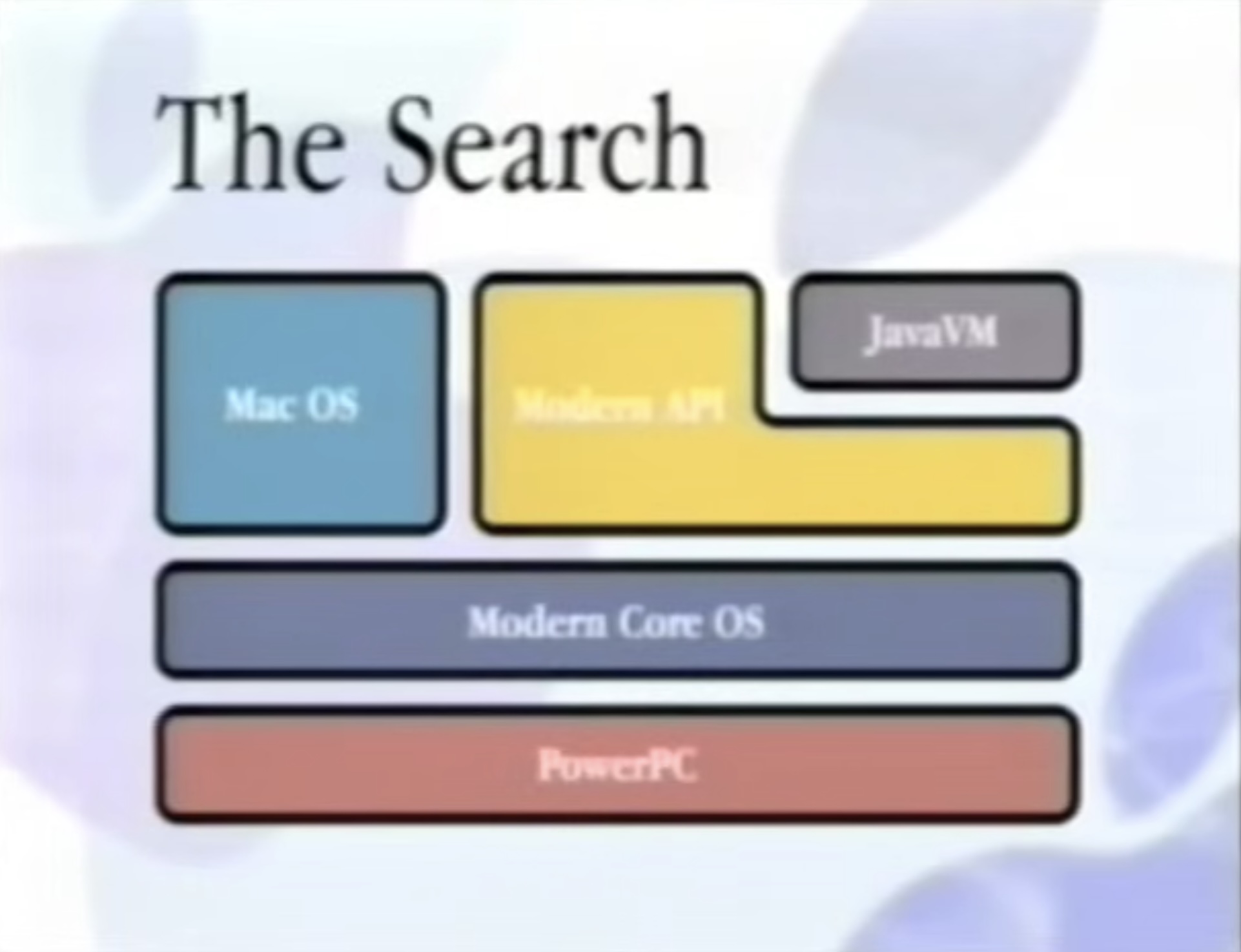

The more I read about the state of the web in the late '90s, the more Java kept coming up. It's a core part of Steve Jobs's reintroduction to Apple, it features heavily in Apple's presentation from WWDC '99; there's a '98 episode of The Computer Chronicles talking about delivering always-up-to-date software via Java websites; the architecture diagram for Apple's new OS for the new millennium features a Java VM on equal footing with their new OS APIs.

It was becoming clear that the web was going to change how software is delivered, and everyone seemed to be scrambling to respond—with Microsoft scrambling to control distribution and Apple factoring Java so heavily into their OS designs.

So what did Java offer exactly? Sun launched it in 1995 with the promise of bringing interactivity to the internet, giving you the ability to add things like "interactive 3-D product demonstrations, live stock portfolio management, multiuser games and up-to-the-second sports information" to a web page. You write code once, and it runs everywhere, as opposed to having to compile versions for each target platform. That sounds similar to JavaScript, which came out at the end of 1995, and JavaScript is what we use for that now, so what's the difference?

Well, consider having a slider as an input for a sketch. JavaScript could be used to get the value from an <input type="range"> element, but that element wouldn't exist in all major browsers until 2013. From when my iMac came out, someone could start high school and finish high school, then start university and finish university, and still have time to spare before they could reliably use a slider in JavaScript. At least initially, it seems like JavaScript was intended for adding quick bits of interactivity to an otherwise conventional page, while Java was the tool to reach for for web applications.

(Aside: conventional wisdom is that "Java and JavaScript are similar like Car and Carpet are similar," but I kind of get it—both tackle interactive web programming, just from different angles.)

Processing: Sketching with Java

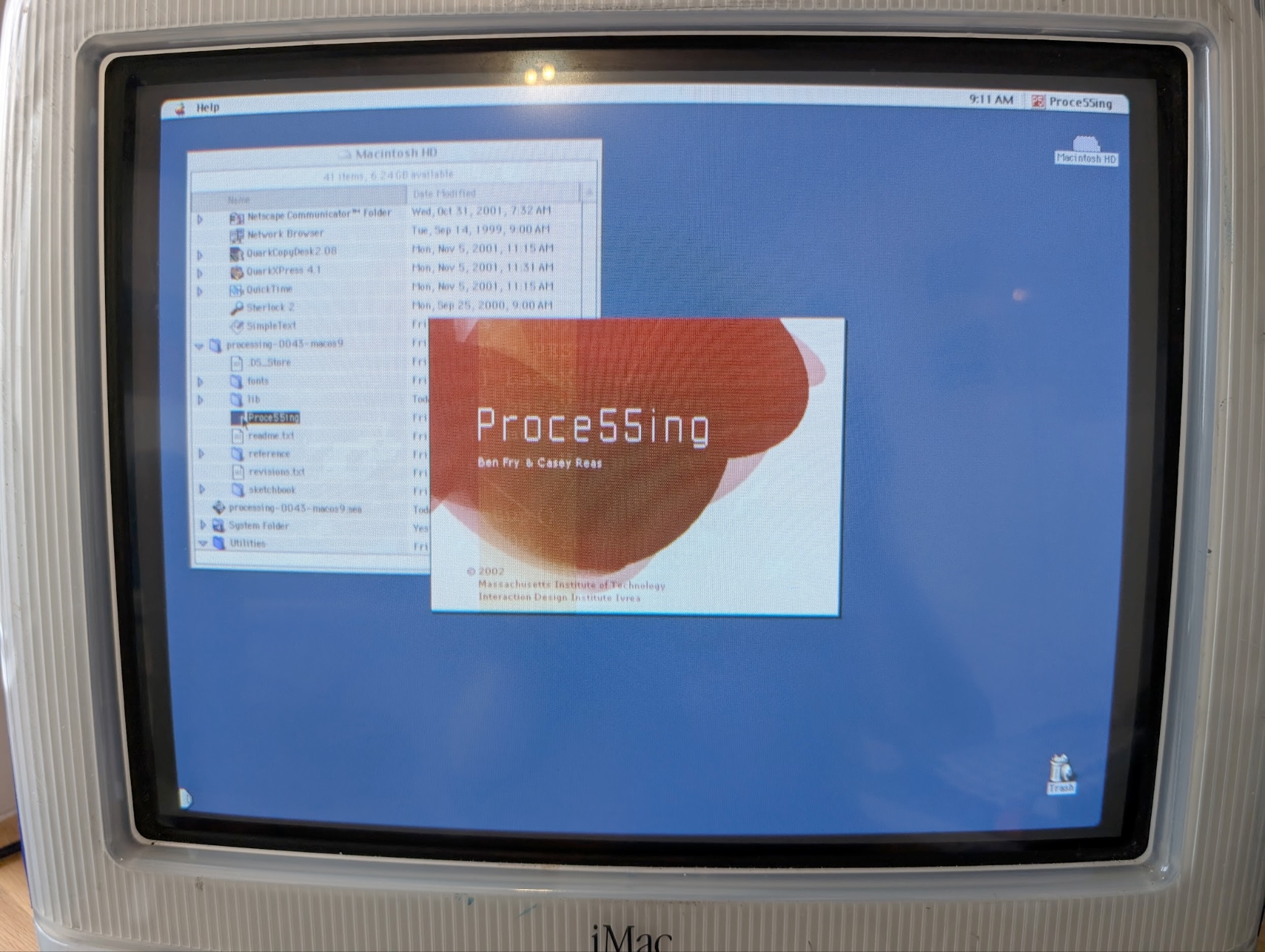

This is the point where a direct forefather of p5.js comes on: Processing. Or, well, Proce55ing, as it was styled when it was first announced (the naming of p5.js today is a callback to that original styling.)

Processing, by Ben Fry and Casey Reas, first came out in 2001, and lives on today. It originally filled the exact same niche as p5.js does now: with it, you can make interactive sketches, and they can run inside a web page. When p5.js was started in 2013, that meant building the framework in JavaScript; in 2001, that meant building the framework in Java.

Installing Processing on Mac OS 9

Getting Processing running again was a bit of a challenge. Support for Mac OS 9 was dropped in 2004, while Processing was still in alpha, since it was a big development time sink and OS X was out by then.

this evening, casey and i decided to set macos9 free. we're letting him go. goodbye little classic mac os. Ben Fry, January 8, 2004

Unfortunately, the current Processing website doesn't include releases that old. The Internet Archive goes back further, but it only goes back to the Processing beta. Thankfully, Processing community lead Raphaël de Courville has access to some servers with old builds! They now live on GitHub if you want to try this out yourself. I ended up installing an alpha build from 2002.

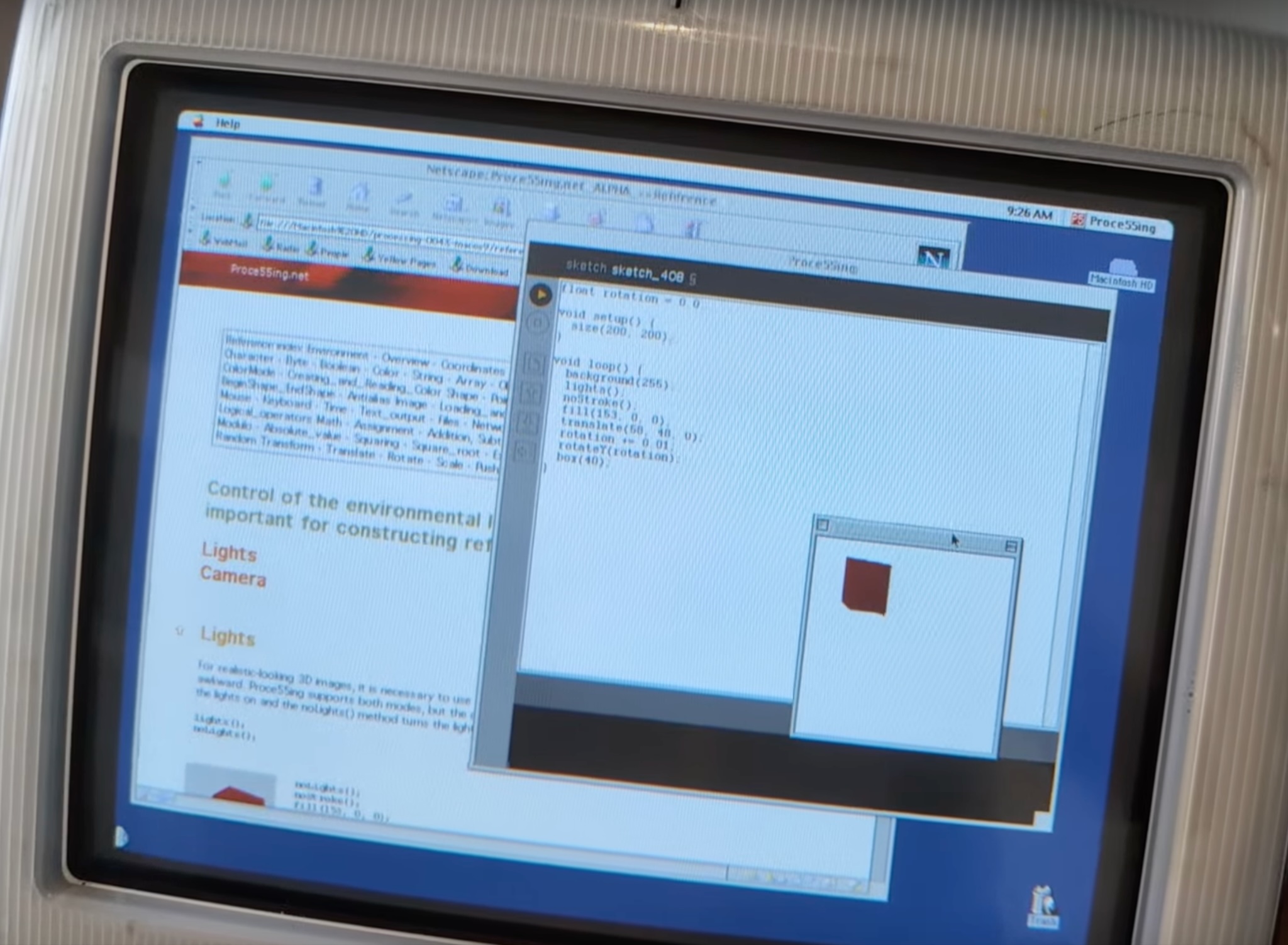

The grain of 2002 Processing

To find the grain of a system, I start by asking myself, what does this system make easy? What does this system make hard?

Procesing has almost no boilerplate if you want to just start drawing lines and shapes. For that reason, many Processing sketches are composed of lines, circles, and rectangles, making those primitives a key part of Processing's texture.

One of the advantages of using code to make art is that you can use loops to draw or animate thousands of objects at once without manually animating them individually. While it's no easier to have multiple objects rather than just one, this ability is a key reason why one would turn to a code-based medium over more conventional software, so Processing sketches often feature lots of details.

Processing has basic 3D support too, so basic 3D primitives with flat or diffuse shading are also part of Processing's look.

Importing images isn't exactly hard in Processing, but it's harder than using basic shapes: you have to create or acquire an image with other software, copy the file into your project directory, import it with loadImage(), and only then can you use it as a texture in your sketch. Since adding an image is so intentional, most of the textures in sketches end up being procedural instead. Perlin noise isn't a thing yet in this version of Processing, so that means uniform random number generators and sine waves end up having the most influence.

Another feature missing in this early alpha build is antialiasing, so pixels will always be crunchy. Computers from this time also weren't graphical powerhouses, so it might not have been worth the processor cycles anyway if you were trying to make a relatively snappy animation.

Not everyone was trying to produce snappy animations, though. Processing was also used often to create intricate still images by building them up slowly over time. This could be done over multiple frames, or even in one long frame.

A great early Processing work by Jared Tarbell, Substrate, shows the kind of detailed texture you can get by layering many, many small shapes.

Flash: Sketching for animation

Processing was big in new media artist circles, but those weren't the only circles doing art on the early web. Many people were also making animations and games and, generally, experiences, using another, even more popular tool: Flash.

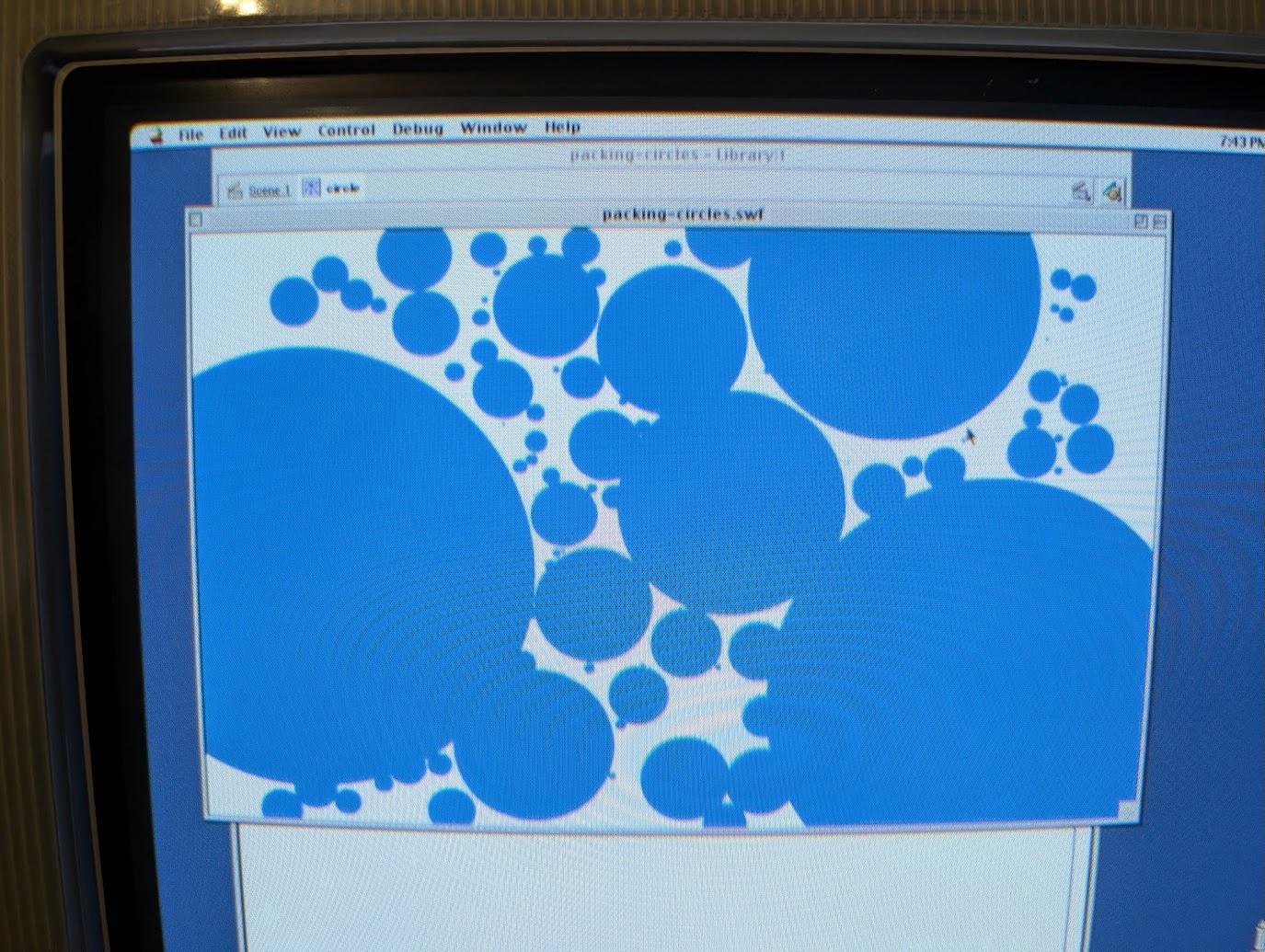

Flash started as vector animation software called FutureSplash Animator. FutureSplash was acquired by Macromedia in 1996 and re-released as Flash ("drop the 'uturesp', it's cleaner") along with, importantly, a free web browser plugin to run Flash content. Early versions of Flash were just for animation. Eventually they added "actions," where you can make buttons that control playback and navigate through scenes using simple forms. Some absolute geniuses at Newgrounds managed to make a game using just these forms. Finally, in the year 2000, Flash 5 was released, which included a full programming language called ActionScript.

Now, you could use Flash to draw shapes in a very similar way as you would with Processing. It works just fine, but it doesn't feel like it's how Flash wants you to use Flash, since raw shape drawing commands are nested a few properties deep.

Instead, it feels more like it encourages you to save shapes as reusable "symbols" that you can then work with as objects in the code.

Flash's real superpower is that you can just draw these symbols! Sure, you could use the circle tool, but you could also grab a brush and draw your own wonky circle by hand.

You also have easy access to the timeline, so you can manually animate your symbols with no extra forethought.

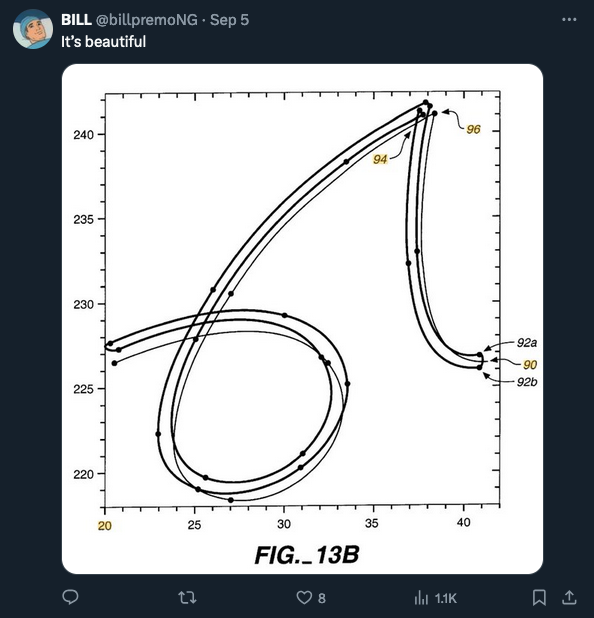

That brush is load-bearing, as far as the grain is concerned. As someone who spent a lot of time on Newgrounds as a kid, and a lot of time in Flash making animations, it's not that hard to clock when something's drawn in Flash. The brush strokes have that characteristic imprecise, charming lumpiness. It has also come to my attention that the patent for this brush expired in 2018 in case anyone is considering reviving it in some new creative software.

The fact that you can animate by hand rather than with code fundamentally changes the balance of what's easy to animate.

On the canvas, it's really easy to reposition and reorient objects over time. Because you can see where you're dragging, you're much more likely to get the look you want than if you were to guess the coordinates in code.

On the timeline, you can easily move around keyframes and preview the animation again to iteratively refine your timing. It's actually quite hard to get a sine wave this way: linear easing is the default, and there are some basic cubic easing controls, but it's so fast to subdivide and refine motion with more linear keyframes that it almost doesn't matter.

This can lead to some really unique "mixed-media" of sorts, where you can use code to make multiple instances of an animation, staggered over time, but where the animation itself is done using classical animation.

The mix of programmatic elements with hand-drawn elements was all over early Flash games.

Again from the Newgrounds folks, Alien Hominid shows a great example of this. Why do an explosion with particle effects in code when you could just draw a sick explosion?

Flash MX 2004 was the first Flash version I used myself (which actually came out in 2003.) It would be a little while yet before I attempted programming with Flash, but I watched lots of Flash cartoons, and was inspired to make my own early on.

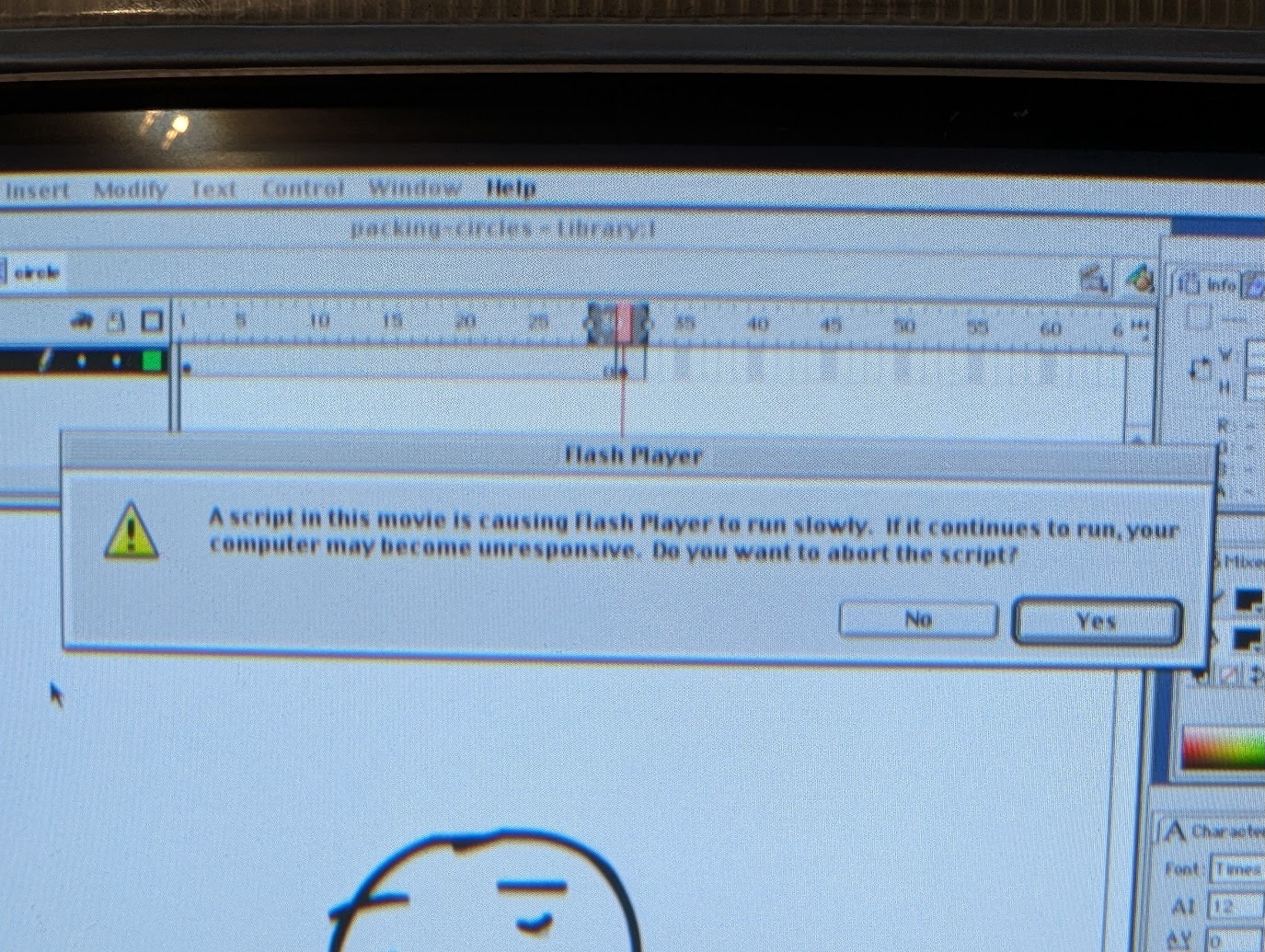

When I did start learning programming, it was through a platformer game tutorial on Newgrounds (distributed as a little Flash slideshow!) Unfortunately I didn't quite grasp every single concept: I didn't understand what a while loop did, so I tried replacing an if with a while to see if it'd magically fix my bugs. Instead, I was greeted with this:

No joke, I stopped using while loops for another two years after this until I learned them properly in high school CS class.

You could also get that message from non-infinite loops, though. Basically any script that ran for too long would trigger it. Flash very clearly does not want you running one long operation, and instead encourages quick real-time stuff. As a result, I can't think of a Flash creation with quite the same level of intricacy as you see commonly in static Processing exports.

Eventually, I returned to scripting in Flash to do somewhat the opposite of what Alien Hominid was doing. Rather than putting hand-drawn elements into a mostly code-controlled experience, I found it useful sometimes to add small scripted elements to my otherwise fully hand-drawn animation, like in this small particle simulation.

While this example is from a decade after the time I've been exploring on my iMac, Flash was largely still the same then, and I was still using the same ActionScript version that shipped originally in 2003's Flash MX 2004.

Where are we now?

The fall of Java and Flash

So obviously we're not still delivering content online via Java applets or Flash embeds. The security problems in those plugins proved to be their downfall, and a few major players throwing their weight behind open standards helped seal the deal.

Everything in the browser now runs on JavaScript now that it's been given access to powerful 2D and WebGL APIs, with WebGPU gaining more support, and WebAssembly allowing other languages to compile to a form runnable in the browser too. The original goal of p5.js was to ask, "what would Processing look like if it were designed today?" and the answer was something built in JavaScript.

What is the grain of p5.js?

p5.js, like Processing before it, still makes it easy to draw using basic shapes and math. It's arguably even more successful than ever at that goal as web editors no longer require software to be downloaded to start creating!

There are some changes to the grain from Processing. As a small example, you basically can't turn off antialiasing on 2D canvas lines, so p5.js sketches will look a bit smoother by default.

WebGL mode has also changed over the years. Its lighting and default shapes make a grain of their own that is distinct from 2D mode.

Shaders also offer a completely different grain, offering pixel-level texturing without use of many tiny shapes.

p5.js 1.11.0 starts to add features to make it easier to start writing shaders, and we hope to keep bringing newcomers into the world of shader art in 2.0 and beyond next year.

Some food for thought

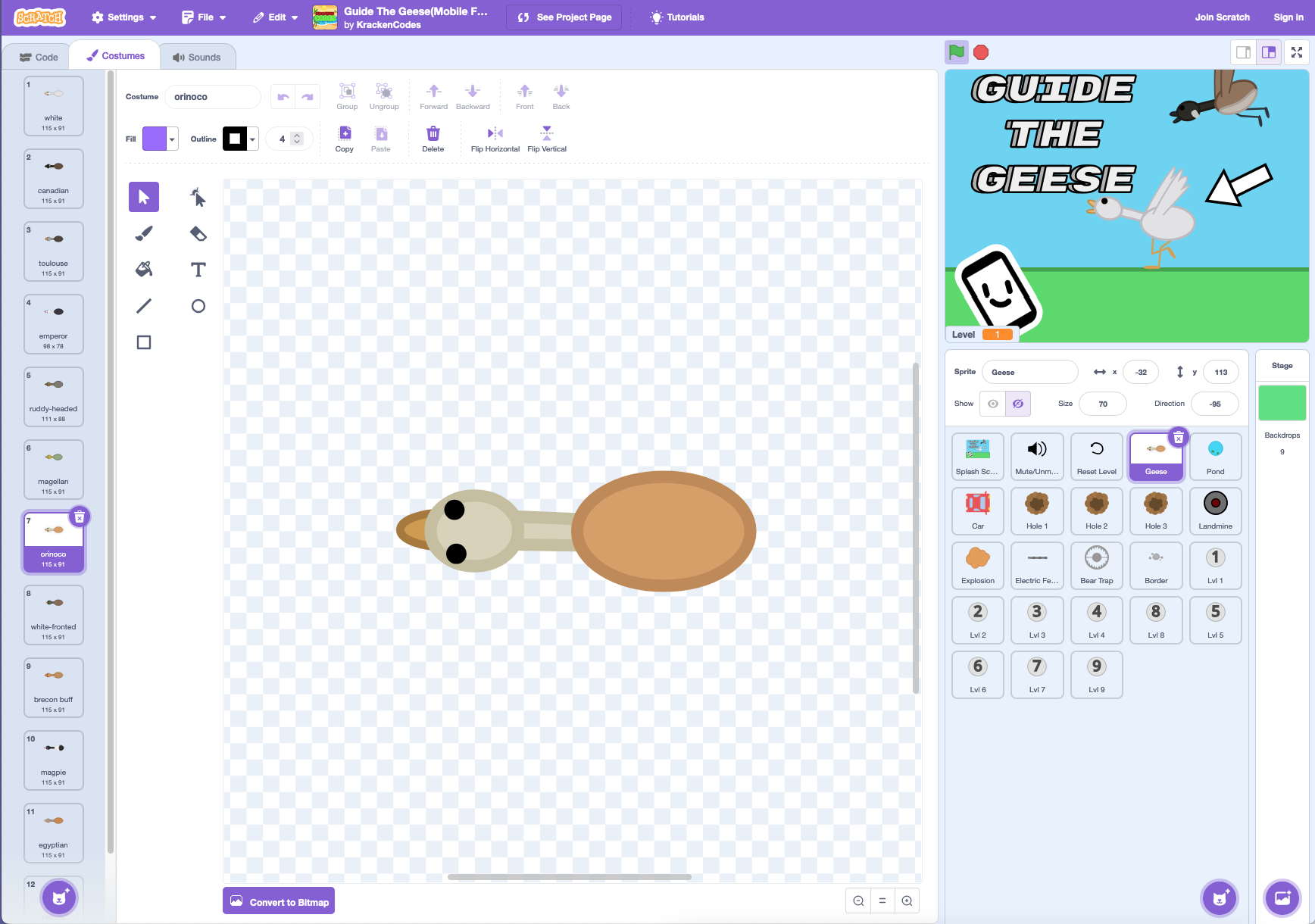

Nothing, in my opinion, has quite matched Flash's ability to mix code and hand-drawn art. Scratch maybe comes closest with its sprite editor, but it still misses the animation piece that Flash had. That said, it flies under the radar for many tool makers as its interface is targeted more at kids, but there's a lot of great ideas in there that shouldn't be slept on!

Anyway, this framing has at least been useful for me for tying the intented goals of a tool to the sorts of work that will be produced by it. I hope I can expand access to some new and exciting grains in the future!